Latest Climate Data & We're Hiring

Some of the latest from talks given by Dr. Elizabeth Wolkovich and Dr. Markus Keller, and more.

Before we get to the main event, a couple quick notes:

We’re Hiring!

Here at Vintality we’re hiring a new precision agriculture specialist.

We are looking for a person who has experience in agriculture, is entrepreneurial, self-motivated, comfortable with selling, and enjoys varied and new tasks. You have the ability to consult and be a value-add for our clients.

Ideally, we’re looking for a more experienced candidate. But because the nature of the work is somewhat unusual, we’re open to hiring to a more junior candidate.

Find out more at https://vintality.com/hiring.

BCIA Nitrogen Management Workshop

If you’re a member of the BC Institute of Agrologists (you just need to create a free online account I think…) you can participate in a Nitrogen Management Workshop they’re hosting.

Scott Smith, myself and Miranda Halladay will be talking about the in-depth soil work we’ve done at Elephant Island as well as their own work and programs. We’ll be focusing on nitrogen management, but a number of topics will be covered.

Find out more here. September 12th @ Elephant Island Winery.

A Growing Climate, A Frozen Climate

I had the pleasure of attending the BC Grape Growers1 2024 “ Grower Day”. It went very well, in spite of my presence on an irrigation panel2, and I was particularly excited to hear from Dr. Elizabeth Wolkovich3 and Dr. Markus Keller.

Given that the Okanagan has had about 50% crop loss in 2023 and 90% crop loss in 2024 (and Washington was also hit, but much less so), a cold climate was the focus of their talk. But one of Elizabeth’s points was… don’t forget the heat! Elizabeth is doing work for the BC industry on varietal assessments and climate modelling, while Markus was speaking more generally about adaptation to extreme cold events.

I’d like to share a few takeaways. I should emphasize here: this is my own view of their presentations and of course I could be unintentionally be misrepresenting their point! Any errors are therefore entirely mine. And a big thanks to both for participating and sharing their knowledge.

Onwards.

A Little Bit Chilly

One of the major points that jumped out was how close some of the vinifera varieties got to hybrids (like Marquette) in terms of cold hardiness. As you can see in the slide below, based on data gathered in the Okanagan, they were almost indistinguishable.

Which quickly brings me to one of the challenges of cold hardiness (we’ve hit on before): the definition changes. There are the cold hardiness in buds, trunk and roots. There is also rootstock hardiness, never mind potential clonal differences. There are a lot of variablities that often get lumped into one big, inaccurate bucket. I think this is also why Washington State’s cold hardiness data can produce “unexpected” results.

This is even impacted by the type of cold. Some varieties harden off at different rates, so the cold hardiness of varietals can change somewhat just based on the type of extreme cold that occurs, say a slow drop or a warm winter to a fast drop in temperature.

The second interesting piece was from Markus on how dormancy is acquired. Specifically, vines enter dormancy primarily in response to day length. Then when dormant enough, they experience “chilling units” which cause them to acquire hardiness. These chilling units are necessary for the vines to enter hardiness and thus the warm winter prevented this accumulation. Interestingly, I believe there was some disagreement between Elizabeth and Markus here. Elizabeth, using Summerland and local data, argued that our plants got about as cold hardy as they could get. Conversely, Markus stated that this was part of why we saw so much damage, as they were unable to harden off enough.

Third, the importance of early refill of the water reservoir. This is because early in the season is when see repair of previous damage due to root pressure removing air bubbles from the system. When we have drier winters, the soil water reservoir may not have been refilled. Further, as the plant begins to grow we see the shift away from reserves to resource acquisition. This necessitates adequate sap flow and water to enable this to happen.

We are huge (HUGE) believers in using water stress to get plants working. No lazy plants! But timing is everything and early in the season we want to ensure there is lots of water for the plant to easily draw on.

Lastly (on cold), a major point that jumped out is the number of freeze events experienced per varietal. As I mentioned, this is because we’re at phenological differences in the climate models. I’m a huge fan of Elizabeth’s approach here! A useful way to think about this (see slide below) is the risk you’re taking with each varietal. The slide shows how with different varietals you’re taking a larger or smaller gamble in terms of freeze events - and how this can be impacted by different regions.

Take time to look at the slide below. The results are quite interesting!

A note: due to the smaller data sets, just for this reason, we see have a wider risk range for Lillooet.

One of the things I’ve particularly appreciated about Elizabeth’s approach is her focus on including phenology in how we model climate suitability. One of her main arguments is that yes, areas may be becoming unsuitable for grapegrowing as currently practiced. But if we begin to swap out varieties, the overall grapegrowing suitability of specific ranges changes less. (This also applies to farming practices, but I think Elizabeth’s argument is that varietal has the largest and most easily delineated impact).

Of course, this brings up one of the issues in current data: current climate models are based on old data. One of my question was “Are we seeing an increase in polar vortexes due to warmer winters?” The concern among scientists here is that the warmer winters allow cold air to more easily flow southwards and thus we’ll see an increase in these events. The current answer is the ever useful “We don’t know”. Our current models will take a number of years to be updated with the latest data and until then it is hard to predict.

My own reading on the research is that it seems this is not the case. I’ve seen some suggestion, for example, that cold comes in two year cycles, and this is not a new trend. I read a paper a few months ago (currently buried somewhere) about how the USA Midwest saw two back-to-back extreme cold events in ~2013-14. Both years saw generally mild winters, and then were hit by an extreme cold. The first year was bad but not terrible and growers failed to fully adapt. The second year they were walloped by an extreme cold from a polar outflow.4 If you had switched the regions and varietals, it was a play-by-play repeat of our 2023-24 season. Of course, this is anecdotal hypothesizing which is the worst way to inform arguments. So take that for all it’s worth.

Welcome to the Heat Dome!

One of Elizabeth’s points (which I’ve been repeating ad nauseaum) is that we’re more at risk of heat than cold. Yes, major freeze events are a massive concern and we need to respond in how we de-risk each winter.5

But our varietal risk is much more on the hot end than the cold. We already have varieties that are about as cold hardy as you can get for vinifera (Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir, Chardonnay, etc.) and there are limits in how far you can manage cold. For example, burying under tarp tunnels such as they do back East will never work here due to our warm temperatures (which isn’t to say cold netting is useless here).

You could of course move to hybrids but the hardest part about wine is not farming or making it - it’s selling it. Further, given both our heat and nature of cold I’m not sure precisely how much better hybrids will do.

One of Elizabeth’s data points was that some varieties will become more at risk due to how the climate shifts the phenological stages. I think irrigation is the #1 farming tool we have, precisely because of the impact it has on phenological stages, so this was quite interesting.

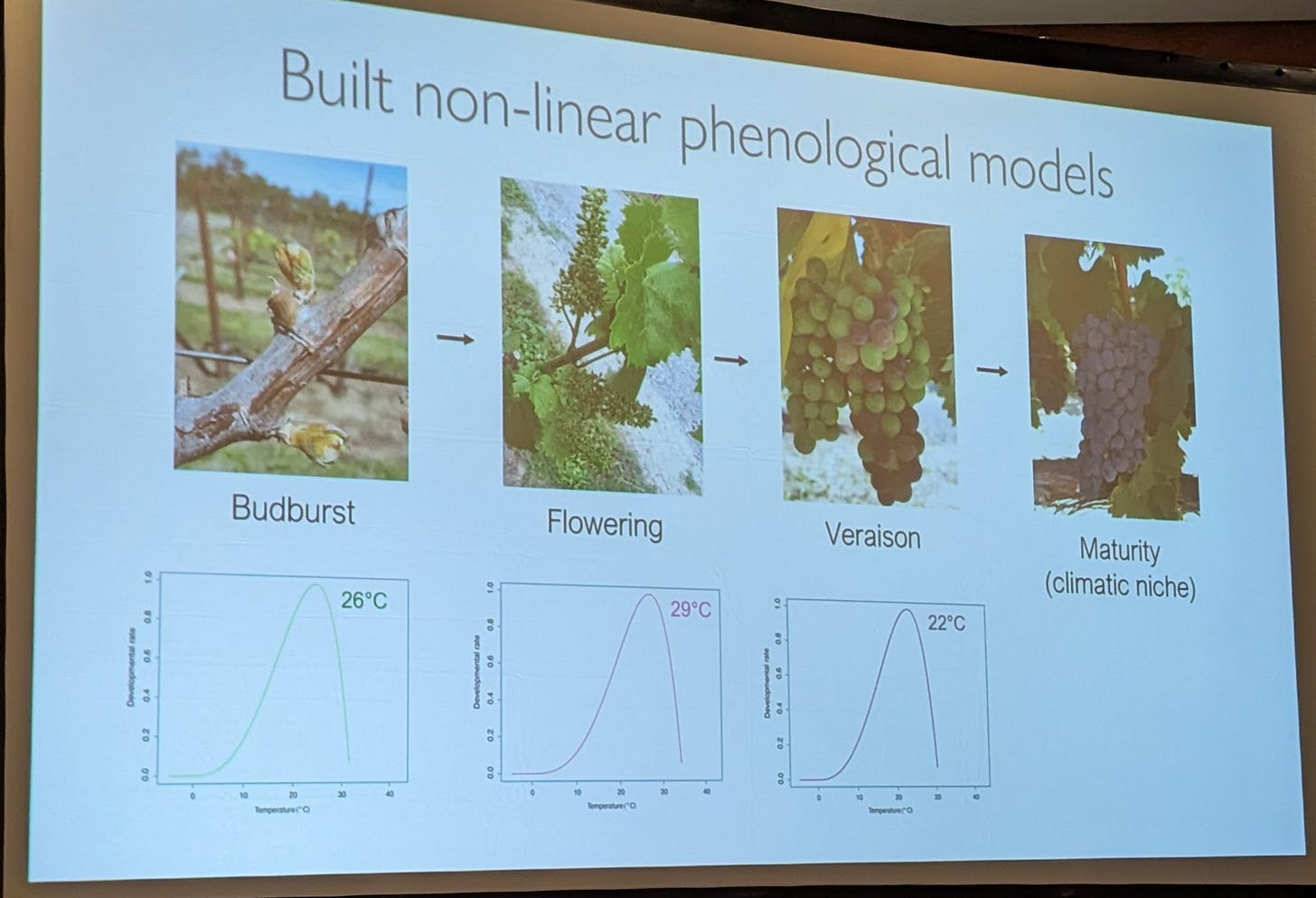

In the two slides below you can see how heat impacts the vine differently at different stages. For example, at flowering the plant does not shut down until around 29°C. But at veraison, this happens closer to 22°C.

This is why we need to use tools to either further accelerate or slow down plant timing. We need to move veraison out of the hottest part of the year or else we’ll have more and more cooked fruit and damaged vines.

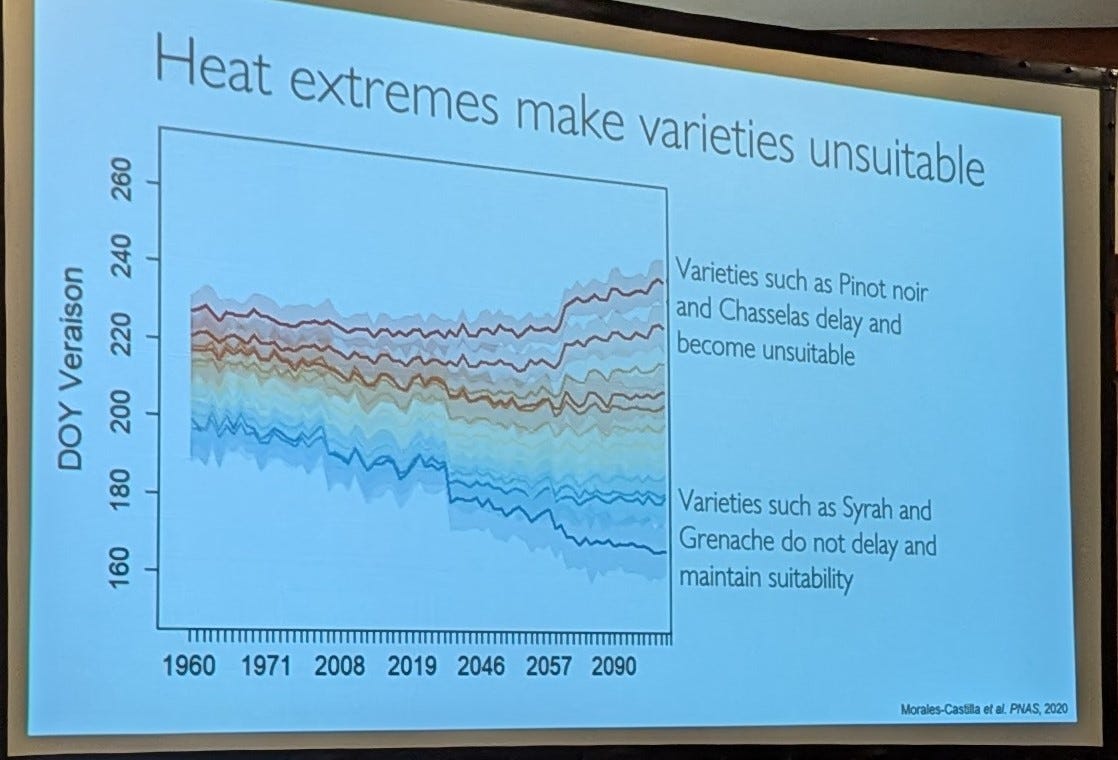

It’s also interesting to think about how heat specifically impacts certain varieties.

Because some varieties, such as Pinot Noir, end up with delayed veraison (and thus during the hottest part of the season) they become less desirable. But other varieties, like Syrah and Grenache, are much less affected.

It is not accidental that these same varieties are opposites in cold hardiness and it speaks to the needle we need to thread. This is another example of why we can’t just look at one trait (eg. “cold hardiness”). There is no free lunch and we have tradeoffs on both sides.

We have both climate extremes. We can’t ignore either and need to somehow thread a needle (and get a bit lucky). My own hope, and it is merely hope, is that these recent extreme colds were merely bad luck not to be repeated for decades. Then we can focus on just one climate extreme. Hope.

“The farmer must be an optimist, or he wouldn't still be a farmer.” Will Rogers

Nevertheless, Nelson Dutra and Roman Kozak did an excellent job on the panel.

Elizabeth has an excellent site I regularly check on, The State of Wine.

What does this sound like? I should also note - this is all true even though they grow hybrids. But of course their extreme low temperatures were still lower than in the Okanagan.

Shortly after the January 2024 extreme weather event, the Summerland Research Station published a graph showing the coldest and warmest winter days for the last 80 years. The spread as you’d expect was on a bell curve with the majority of hot/cold days clustered around the average. However there were also a significant number of extreme cold days (< -20C). In other words, such events in the Okanagan aren’t rare but normal, if irregular.

Assuming that pattern continues, it seems unavoidable that Okanagan vitus vinifera growers will have to renew their vineyards from time to time. This could mean restarting vines that have sustained top damage, or replanting vines that die outright from the cold.

At our latitude we’re pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with Vinifera. So planting a vineyard in the Okanagan does not seem to be a ‘once and done’ proposition.To remain economically viable long term, growers will have to plan for weather related setbacks that cause serious vine damage.