Why are you planting rootstocks? Should you own-root?

Something of a treatise. Don't shoot the messenger! (Or do, I'd only deserve it).

News and Events

Vines to Vintages is holding an event today (Nov 26th) as a “Fortify-lite” to replace that cancelled conference. There will be vendors, snacks, and talks. I’ll be speaking at 2pm on “Advanced Terroir Mapping and Sensing Technologies.”

The even is going from 10am to 4pm at 445 Warren Ave, Penticton.If you are an Okanagan farmer, a reminder that with Growers closing you will need to be more on top of vineyard purchasing. Everything won’t immediately be available, and with the port strikes, threatened rail strike, Chinese tarriffs on steel, threatened US tariffs, and steel prices increasing in January get your orders in now.

A reminder to register for the Southern Interior Horticulture Show here.

A reminder the Enhanced Replant Program closes on December 3rd. Yes, it’s a bad program and yes very few farms are applying.

Rootstock, I hardly knew you

For those less familiar with the industry - rootstocks are literally what they sound like. Non-vinifera vines onto which vinifera like Chardonnay or Merlot are grafted onto. So a vine will have a root of say vitis rupestris onto which a vitis vinifera vine (eg. Chardonnay) is grafted. The rootstock gives the vinifera characteristics it lacks, most popularly phylloxera resistance.

The honest answer is that, in irrigated settings, we have very little idea what characteristics rootstocks have.

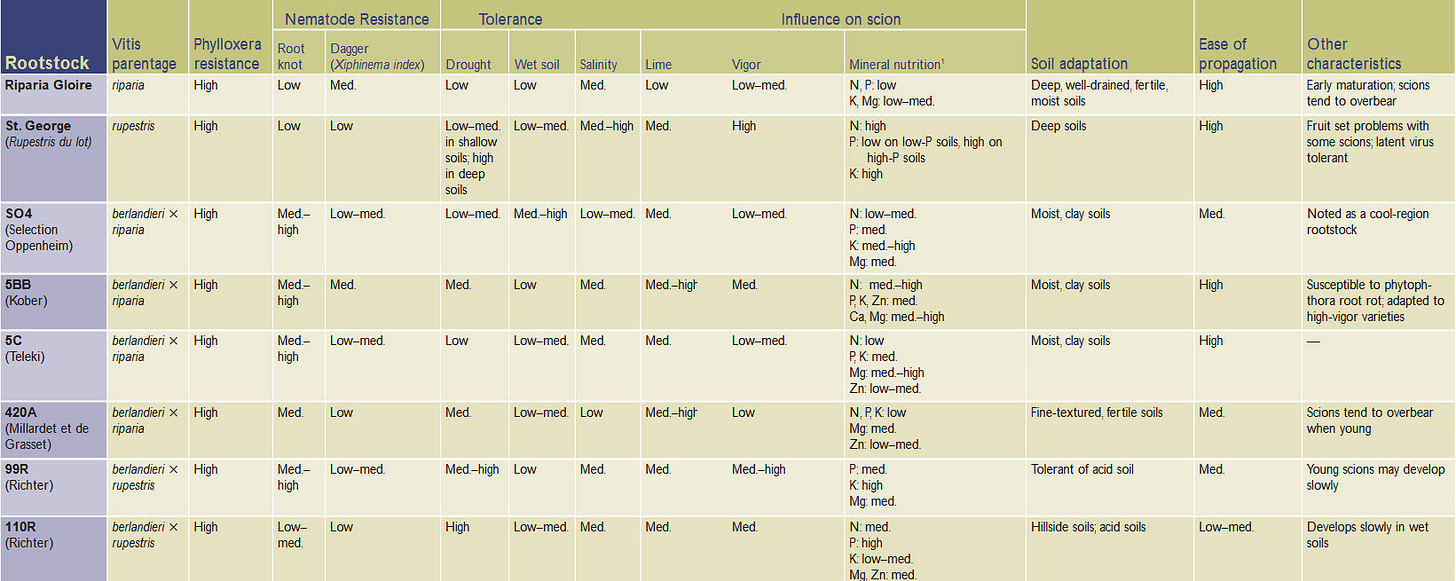

You might be familiar with tables like this:

Yet the problem is that once we introduce irrigation - that behaviour goes right out the window.

I’ll give you a perfect example, Riparia Gloire. This is a ditch weed-type vine that all the literature tells you loves water, can’t handle drought, and needs fertile and moist soils.

Except I can tell you, without a shadow of doubt, it’s bullshit. Why?

Because I’ve seen Riparia planted in pure sand in 40 degree heat with VPD numbers that rival the deserts of Portugal that is thriving. In fact - outperforming other popular rootstocks like 3309C and SO4. Per these tables it should be struggling.

What is happening?

Down another rabbit hole

Markus Keller gives us a clue:

In Washington’s deficit-irrigated systems, most of the differences in terms of rootstock performance will be minor. There’s lots of published information about rootstocks out there, from nursery tables to books, but it’s hard to glean exactly how a rootstock will perform in one location from elsewhere. Some of the commonly cited tables include information from potted vines or rootstocks that are growing ungrafted.1

If you’ve ever read rootstock descriptions in depth, you’ll often find contradictory information. Often in the same description!

For example, let’s look at a specific characteristic - rooting depth.

I can’t speak for regions that can practice widespread dry farming, I’ve neither worked nor studied these effects closely. But I can say that in an irrigated setting these rootstocks rooting practices do not fit with neat descriptions.

This of course makes sense. Let’s again take Riparia that supposedly has a wide branching root system. Well, what happens when you put it on drip on sand from “birth”? With long sets that water will go straight down in a column. Do you think the vine will just give up all that water and branch horizontally rather than down?

And this is what we see in research data:

The data suggested that soil properties such as the presence of soil profiles impermeable to root penetration, stoniness, and presence of gravel lenses have a greater influence on depth distributions than does genotype, even in deep fertile soils. Genotypic differences were not apparent… The analysis also suggests that root characteristics other than root horizontal and vertical spread may need to be considered in order to explain some key rootstock characteristics like scion vigor or drought tolerance.2

That is, the characteristics of the soil have far more impact on rooting behaviour than the rootstock itself. And this is not even factoring in irrigation.

We can also return to one of Keller’s points - the research on rootstocks are not only often conducted in non-irrigated settings (especially in France) but also on the full rootstock itself - not vinifera grafted onto that rootstock.

Further:

In this regard, Renouf et al. (2010) showed that the potential quality of a soil can be improved by the correct choice of rootstock, but in soils with lower potential quality, the rootstock genotype cannot compensate for the loss of grapevine performance, since root distribution is mainly determined by soil properties, while the rootstock modifies root density and root activity.3

One of the factors we can certainly say is that rootstock behaviour is trumped by soil characteristics. For anyone planting I would encourage you to spend more time exploring your soil for the affect it will have on your vines and less on stressing about rootstocks.4

Again, returning to Keller we can again see the inherent nonsense of a lot of rootstock characteristics":

However, 3309C was the rootstock associated with the highest pruning weights in Syrah and the lowest in Chardonnay. Rootstocks usually did not impact vine phenology, fruit set, and plant water status, although there was a trend for stem water potential to be highest with 3309C and lowest with 5C. The rootstock effect on yield formation depended on the scion cultivar, and variations in different yield components often cancelled out each other, but 3309C (Merlot and Syrah), 5C (Merlot and Chardonnay), and own roots (Chardonnay) were often associated with high yields.5

Italics mine. This paper is again pointing out that once vinifera is introduced, the results change. This study included irrigation, occurring down in Washington, found contradictory results on rootstock - both within the trial itself (for example 3309C’s vigor changed drastically based on cultivar) and against other research.

Why rootstock?

Now there’s a whole other piece we haven’t touched - phylloxera and nematode resistance. Here, I suspect we are on firmer ground. But to be clear - I have not studied this closely. We know phylloxera resistance from rootstocks has worked and I can only assume that it is similar for nematode resistance. But at some point I’ll have to do some more digging.

This also fits with irrigation being a major variable, as it would not affect the mechanisms that confer pest resistance.

There are other factors, like nutrient uptake and cold hardiness, I’m not even going to touch here. I am extremely skeptical of this data, especially nutrient uptake, but have not studied it in depth. I suspect most of the research occurred on non-grafted plants and is dubious.

I do suspect there is a rootstock effect on salinity tolerance. We have seen 3309C, supposedly susceptible, get smacked by salinity issues where other more tolerant rootstocks (per the literature) were not.

As for vigor and drought tolerance? I believe the results are mixed. There is some vigor affect. I do believe, for example, that SO4 is typically more vigorous. But again - this can be trumped by many other variables.

And this is where my self-skepticism comes in. Do I think SO4 is vigorous because we over-water and I am seeing those results? How would that change in more properly managed deficit irrigation vineyards? Certainly, SO4 is not vigorous everywhere I’ve worked…

However, our measures of vine vigor, such as shoot number, cane weight, and pruning weight, suggested that own-rooted vines were more vigorous than were grafted vines and 1103P consistently induced low vigor; 5C was often grouped with own-rooted vines and 140Ru with 1103P. The >50% higher shoot number of own-rooted Merlot and Chardonnay compared with grafted vines was especially striking. In contrast, 3309C was associated with high vigor in Syrah, intermediate vigor in Merlot, and low vigor in Chardonnay.6

So if you care about vigor, should you own-root as this study found own-rooted were the most vigorous?

Should you own-root?

No.

Just kidding. This is complicated, but I think we can simplify this decision.

What is your greatest risk? After the Okanagan freeze events of 2023 and 2024, if cold damage is the major risk then own-rooting gives the benefit of easier recovery through renewal and layering.

But I would strongly encourage nematode and phylloxera testing to mitigate this risk. If you don’t - results could be catastrophic financially.

The trade-off is the benefits that rootstocks bring. But per the Keller paper above, perhaps if you want more vigor you get better results from own-rooted? Or perhaps those results are only applicable to Yakima.7

And this is something I haven’t even touched on, vigor =/= yield!

Often we see discussion of vigor and rootstock. But I see many people (understandably) automatically associate vigor with yield. But this isn’t the case, especially with rootstocks and we see this throughout the literature. Yield results are inconsistent.

Vine yield, cluster number, berry weight, berries per cluster, and cluster weight are under the control of the scion cultivar. Rootstock had no measurable impact as evidenced by the lack of statistically significant change in these parameters over the same scion on different rootstocks.8

Ultimately, I think the decision comes down to what the greatest risks are, not just now but years down the line. There are risks and the decision should come down to minimizing those risks. And if you have a successful history with a rootstock there then don’t rock the boat.

How we make rootstock decisions

The honest reality is that anyone pretends they are certain what rootstocks you should choose and what exact characteristics the rootstocks have is just wrong.

We know rootstock behaviour is heavily modulated by soil, climate, scion, irrigation and general vineyard management. We just can’t be certain, especially in our irrigated settings, how these rootstocks will behave.

Local knowledge and experience matters and I would listen to someone who has had sustained success with a rootstock on a very similar site. But I’d also test to make sure they fully understand their pruning, irrigation, and broader farming strategy. Otherwise they could be recommending a rootstock that worked because of how they unintentionally irrigated or even just the climate over that period.

And even where you think you have seen X or Y characteristic, you may just be you telling yourself stories. We are storytelling machines more than anything and will look for ones where none exists. You and me both!

I do stay away from research done in France purely due to irrigation. I’ll look to ideally Washington, but also California or Australia (whose research is excellent), to try and find similar soils and climates to compare to.

Generally, I prefer lower vigor rootstocks as most of our clients are focused on premium production. As well, I think it’s much easier to “up vigour” a vine than slow it down. But again - this is based on the same mediocre lists out there and may not be true. An interest in 1103P may just be based on bad data.

Edit, Dec 2nd: I received an interesting comment on using 1103P over concerns that it delays ripening. Where you’re using a varietal that is at risk of not ripening in time this would be an unnecessary risk. But reading the published literature on 1103P with grafted vinifera, I found data showing ripening delays from 0, 2, and 6 days. Ultimately, I think this data shows again that management trumps rootstock characteristics.

Obviously, if we have concerns about nematodes or phylloxerra that simplifies things. Inversely, if cold risk is judged the number one concern that does too.

Ultimately, I am honest about the shortcomings and do my best to make sense of incomplete data. I do not pretend to be a rootstock expert (because I’m not), but like many things in farming I’m surprised to discover how few true experts there are!

And so I say, good rootstocking!

Disagree? Am I woefully wrong somewhere? Totally agree? Please - let me know or leave a comment here as I’d love to interact on this topic. By no means do I have it figured out and there’s lots of knowledge out there to share!

https://www.goodfruit.com/rootstocks-a-new-reality-for-pacific-northwest-vineyards/

https://www.ajevonline.org/content/57/1/89.short

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0378377423004250

That’s not to say you shouldn’t pay attention to rootstock choices! They matter. But they are trumped by soil.

https://www.ajevonline.org/content/63/1/29.short

https://www.ajevonline.org/content/63/1/29.short

Per this article’s thesis, the results are not consistent with other studies showing rootstocks increasing vigor. For example: https://scijournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jsfa.9496

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15538362.2013.789277